By Ambassador Annalisa Van Den Bergh

At the Whitefish, Montana Train Depot, after a summer cycling Glacier’s Going to the Sun Road, I lift and hand my Kona Sutra to a conductor in the baggage car of my Seattle-bound 14-hour Amtrak train. It’s one of those small town, old-timey train stations where the platform is level with the rails and the waiting room features a taxidermied mountain goat. I board the train and press my forehead against the window, watching golden hour sparkle over mountain-lined lakes then fade into darkness. In Spokane, I repurpose a surgical mask into an eye mask and let the train’s trundling cradle me to sleep.

I wake up from a surprisingly full night’s rest in Leavenworth where I’m joined by a sweet grandmother on her way to the coast for a getaway amidst constant care of her sick husband. I love train rides because you meet people from all walks of life. We chat until we hit the Puget Sound and then I switch trains for Eugene where I give my friend Olivia a big squeeze.

This mini-bike trip is a voyage to a personal mecca of mine. There’s a part of the TransAmerica Trail that I skipped when I took the Lewis and Clark shortcut in 2017. From what I’ve heard, the central Oregon section I missed is not only one of the most beautiful stretches of the popular route, but also features the world’s most bicycle friendly hostel.

The few-day ride across central Oregon to get to Mitchell, the town where the hostel is located, is a bittersweet mix of wildfire remnants and gorgeous, sweaty climbs. It doesn’t take long for me to leave Eugene’s city limits and find a burger and fries along the McKenzie Highway. I ask for the check and find out that the lovely ladies sitting next to me paid for my meal, a common occurrence on bike tours but not one I’d expect on the very first day!

The next day, it’s a long, zig-zag up to McKenzie Pass but the reward is a surreal 3,000-year-old lava field frozen in time. Then, a 50-mile ride through a heatwave and into the town of Prineville where I let myself into a stranger’s house and enjoy a cold shower. This is not the first time I’ve done this but for me, the novelty of it never gets old. It’s all thanks to Warmshowers which is essentially the CouchSurfing for adventure cyclists. If there was ever a beacon of hope for humanity amid a never-ending news cycle, it’d be Warmshowers.

A few hours after I arrive, I meet the family the house belongs to: a Québécois couple and their three girls who just came back from a birthday party. They walk in and immediately treat me as if I’m part of the family, telling me about their day at theatre camp and sharing stories from previous Warmshowers guests. Most striking is their impressive guestbook, stuffed with postcards and photos from five years’ worth of cyclists. To me, it stands as a testament to how rich our lives can become when we let folks in.

My last day of riding is a quick climb up Ochoco Pass and into the arid, hot, painted hills and tiny ranching town of Mitchell where, at last, I reach the Spoke’n Hostel. In 2015, hosts Pat and Jalet Farrell moved the pews of their church one floor down and turned the assembly room into a bunk room for cyclists and car travelers. The hostel’s hype is heard as far as the other end of the TransAm in Virginia, and for good reason.

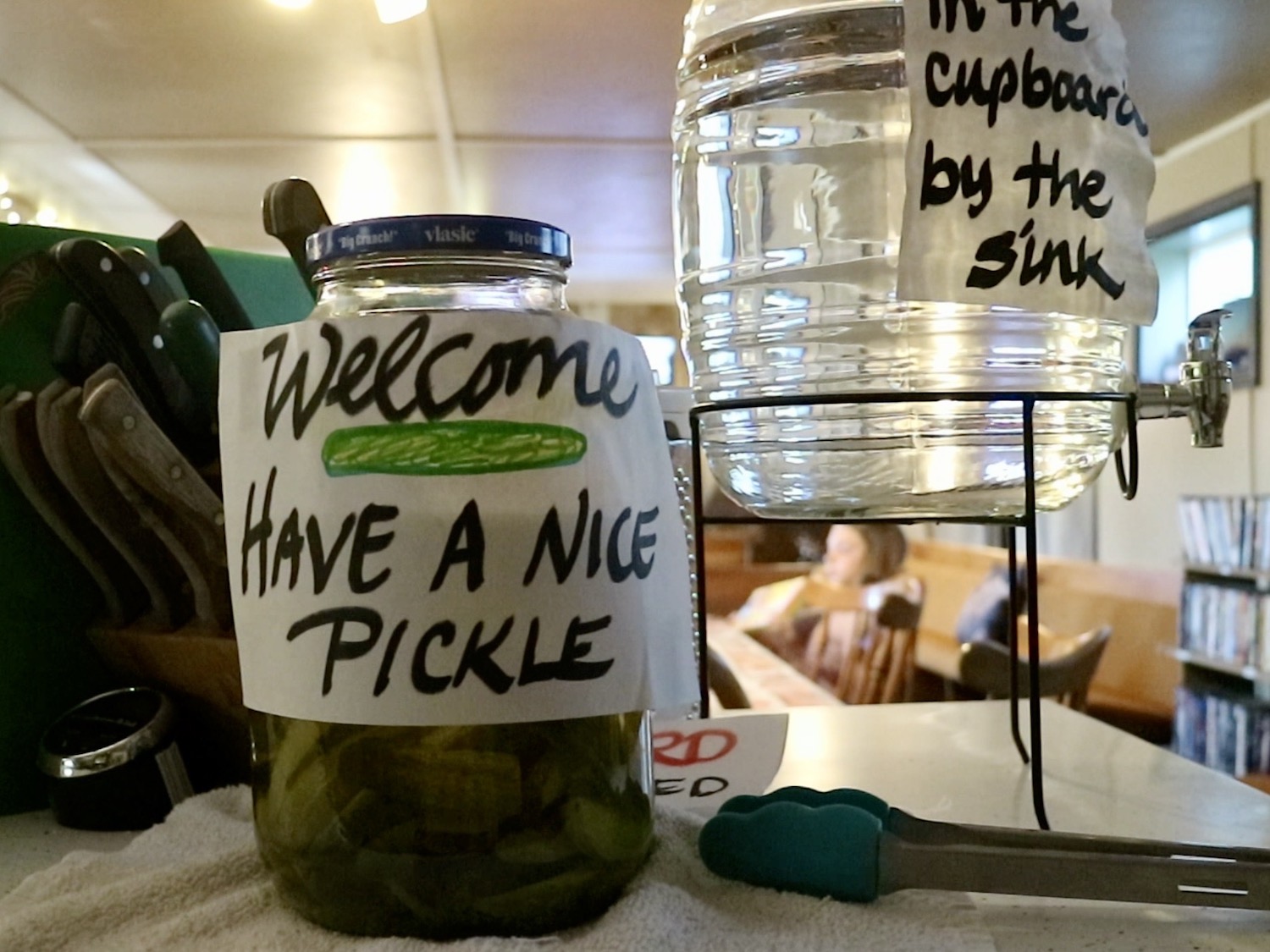

Walking into the Spoke’n Hostel is like coming home. A jug of water for the passerby sits outside the building and a sign on the door invites you to park your bike at the foot of your bed. I enter the building and Jack Johnson is playing softly in the bunk room. It’s one of the many small details Jalet has thought through: ‘We put on music because I don’t want guests to feel like they are disturbing anyone by making noise as they settle in.’ Maite, a tween member of the Reyes family who are subbing in for Pat and Jalet while they take a much-deserved rest, gives me a quick tour of the place. Her hosting abilities are both mature beyond her age and adorable.

I decide to stay four nights because I’m filming the hostel’s story for an upcoming project but also because I know that parking myself here for a bit will allow me to live vicariously through cyclists riding the TransAm, a route that’s very close to my heart. I reminisce over spaghetti with recent high school grads, retirees, and nurses about interesting characters from long-gone places. We’ve stayed in the same abandoned church in Wyoming, jumped into the same swimming hole in Missouri, and (probably) got chased by the same dogs in Kentucky –– just at different points in time. Everyone comes with a different perspective and a different reason for riding this route and that’s what makes it so special.

The hostel is and always will be donation-based. No one will chase after you and ask for your payment; simply put what you can in one of the collection boxes or donate online. It’s always been in their ethos to do it this way so that if you aren’t able to give too much, you can spend that money in town on food and towards the local economy. The average donation still comes out to be $25 per night because cyclists value the hostel and want to see it succeed.

I sit down for an interview with Pat and Jalet. Their love for the cycling community runs deep despite never having been cyclists themselves. When they started the hostel a few years ago, they had no idea their front doors opened onto the iconic TransAm Trail. But it was sort of meant to be. Jalet shares: “We have been adopted by the most gregarious, welcoming, and appreciative family called cyclists outside of any expectation we ever could have had. It’s a bit blindsiding and it’s wonderful. I never know what’s going to walk through the door, but I know they’re hot and I know they’re tired and I know they want a bed and I’ve got all of those things. So it just makes the friendship start right away.”

Pat chimes in: “I always laugh because we say that cyclists are the most overachieving lazy people in the world because they come in and they just kind of hang out. They’re so laid back and relaxed and then they get on the bike and they’re just climbing hills and I just think, that is nuts.”

Like the hostel itself, Pat and Jalet are some of the warmest, down-to-earth folks you’ll meet. They are true trail angels in every sense of the term. With the help of Doug and Donna Strange, during the 4,200-mile, self-supported Trans Am Bike Race, they stay open 24/7 for about four days straight, cooking pasta and ringing cowbells all, as Jalet puts it, to help fulfill the dreams of every single racer. “It’s an honor to be a part of it.”

On the last morning as I’m getting ready to leave for the airport, I run downstairs to grab my insulin from the fridge and smile as I read a quote that someone has written and posted across the door:

“I thought it would be about the journey; I learned it was all about the people instead.”

All images by Annalisa van den Bergh